Delays are regretful yet reasonable expectations to have of ambitious video games. I recall anxiously anticipating Super Smash Bros. Brawl and roiling in agony each time it was pushed back. However, I had too much time on my hands since I was lamenting over two delays that only lasted three months total. This is nothing compared to others waiting a year or longer for Below, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Rime, or Star Citizen. As of the publication of this review, they’re experiencing woes pertaining either to creative disagreements, financial crises, technical holdups, or just being daunting undertakings. These hitches happen, but at least progress is visible. The same cannot be said for paragons of development hell, which have struggled with worse circumstances like studio fallouts and unprecedented revisions.

Resident Evil 4‘s original build by Hideki Kamiya evolved into – get this – Devil May Cry, and only found itself after several versions of the game were scrapped. When Shinji Mikami took on directorial duties, he was able to bring about the survival-horror game that boldly brought action to the series after six years of slow refinement. 2016’s DOOM would‘ve never existed if a previous project, the uncharacteristically cinematic and narrative-heavy DOOM 4, hadn’t been discarded in 2011. John Carmack and various employees left id Software. Studio morale and cohesiveness were low. Discussions of shutting down the historic developer were supposedly had. Despite the odds, id adapted and conquered with a self-aware, confident overhaul that returned the series to its roots. I can personally tell you that eight years of patience paid off. Of course, other games have been less fortunate. Developer Silicon Knights conceived the idea for Too Human in 1999, but floundered on the new IP by switching partnerships from Sony to Nintendo to Microsoft. Nearly a decade later, it’s no wonder it arrived to average fanfare. I could also cite Duke Nukem Forever, but need I elaborate on how a game in production for about 14 years turned out in Gearbox Software’s possession? Don’t try me.

The Doom Slayer lived.

Seeing how these games panned out over the years…isn’t the timetable of releases fascinating? I like to think of it as a flowing stream. We wade in its perpetuity downstream, walking past or picking up games we see in the water along the way. Each step is a day down this metaphorical river of time, and while we may constantly stroll up to new discoveries, some games lodged in the fallen branches and protruding stones of the river’s bedrock don’t always stay in their original places. In times of turbulence, they drift further down the river due to rising waters and violent undulations, only to tentatively nestle in the sand along the bank or be caught on another obstruction. We may get to them one day, but sometimes they sink, never be seen again. Sometimes they float forever in time, unable to break away from the stream’s tide. Sometimes, when games submerge from sight, become too distant, or morph into legends, they emerge. They cease drifting. They are suddenly within grasp!

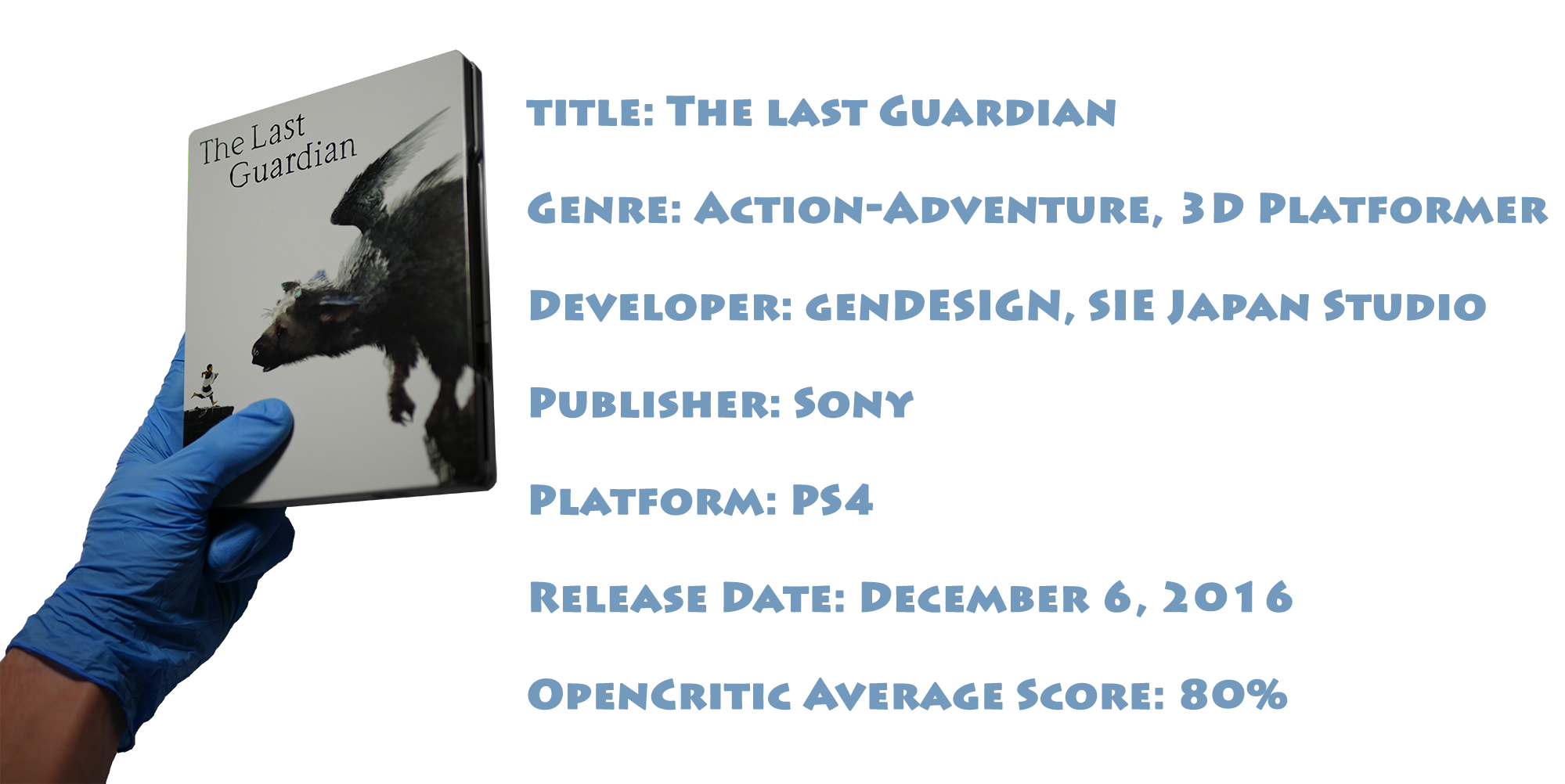

Last year saw this miracle occur not only with Final Fantasy XV, but also Fumito Ueda’s The Last Guardian. It’s been in production for nearly a decade, switched from the PS3 to the PS4, and was nearly canceled. There were grave technical issues on the PS3 with the frame rate and processing. Ueda even left Team Ico to form his own studio, genDESIGN, for unknown reasons. Still, he continued his work. Sony provided support after his departure. Nothing was in this visionary’s favor as he toiled to make his dream game a feasible reality for years, but when everyone lost hope, The Last Guardian persisted. Now, the impossible has happened. It has surfaced, finally coming to rest in the river. We’re able to reach out and hold it in our hands.

How To Train Your Trico

YouTube Version At The End

Story

To give a synopsis is…unfitting. Ueda’s games are renown for their ambiguity and subtle storytelling. Sparse dialogue offers mere glimpses into the lore of his creations. Vague environmental storytelling hints toward myths and mysteries that can only be inferred through keen interpretations. Even connections between all three of his games are meticulously debated, but Ueda must be appreciatively amused by it all. In an interview, The Guardian’s Keith Stuart wrote, “He exudes this air – whether manufactured or not – of winging it. Ten years ago […] he claimed that while studying art at university he specifically chose to specialise in conceptual art for the main practical component so that he could get away with bashing together something abstract a day before the course deadline. Of course, no one could accuse him of bashing his games together, but he retains the self-deprecating air of the chancer who made good, who is almost mystified by the meaning that people ascribe to his work.” 1 We’re always searching for deeper meaning in art we observe, but sometimes there’s less than we assume there to be.

The key is to make it seem like this isn’t the case, and that’s where The Last Guardian is profoundly successful by heavily encouraging players to personally invest in its story. You can summarize its story as a boy who’s been taken far from home, seeking to return with a beast’s help. That’s the bare premise, but what on earth is this chilly, white room you stumble across at the beginning? Why is there a giant tomb inside decorated with a reflective shield that can command Trico to shoot lightning from his tail? What are these magical runes that these automated stone guardians send out to obscure your vision? Do these symbols relate to the tattoos across your body, and do they have something to do with Trico?

There’s more than one “Trico” out there. Their imposed destiny is antithetical to how your Trico relates to you…can he overcome it?

There are more questions I was mulling over, but I never felt frustrated in receiving little answers. You see, there’s a key difference with games that tease and imply you’ll figure things out since the mysteries feel like key parts of the narrative. You expect some degree of revelation. When this doesn’t happen, it’s like having someone tell you to get hyped for something behind a curtain, but when they pull it away, there’s nothing to see. What The Last Guardian does is focus on your adventures and the relationship between you and your beast, whereas the strange explanations behind the world are a backdrop meant to be speculated. Your views of the ancient ruins you explore, Trico’s purpose, the stained glass windows that disturb him…clear-cut answers would spoil the mystique surrounding them.

Ico is about a boy rescuing a girl from imprisonment. Shadow of the Colossus is about resurrecting your loved one by defeating giants to appease a god. Simple motivations drive your emotional investment in these games’ characters, and the same applies to Ueda’s latest, possibly in the strongest way yet because of how the animation and mechanics contributed to my connection with Trico.

Gameplay

Team survival is a curious thing. Strangers might be willing to cooperate or help others if they mutually benefit, but when a potential act of selflessness rears its head, we’re prone to back off from making it reality. We’re creatures out for ourselves, and while teamwork is wonderful, we transcend our instincts and base natures by giving without receiving. Jeopardizing our safety or comfort to uplift another. The Last Guardian illustrates the growing altruism between Trico and the boy in an imperfect yet realistic process through its gameplay. This in part comes from the risky decision to design Trico as an unpredictable AI, which results in frustrating moments where he might not do what you want or misinterpret where you direct him. This is prone to cause doubt about whether you’re barking up the wrong tree with a puzzle, when, in fact, your original suspicion is the right solution. Trico just isn’t listening. Sometimes he can outright refuse you, which resulted in awkward restarts for some journalists who previewed the game before its release. It’s also a good reason why live demos were never performed because Trico is unruly. Independent. Untamed. He’s an animal after all, and that’s what you expect from the wild ones.

Trico never does anything out of character. He will pause and think about what you’re asking him to do. He’ll even call to you and point with his head to help solve puzzles! Other times, he will immediately understand what to do without your guidance or be clueless. That’s what makes him believable.

How do you go about reviewing design that’s meant to be intentionally inconsistent? If Ueda himself is aware of the annoyance this causes and desires players to experience it, can this be equally panned like the programming for Shiva in Resident Evil 5 or Tails in Sonic The Hedgehog 2? I’ve found this to be a severely subjective kind of criticism, so in The Last Guardian’s case, I welcome the imperfection because it’s important to how you treat Trico whether he obeys you or not. Do you console him and wait patiently when he doesn’t listen, or do you ignore him and spam command buttons out of rage? Do you take time to pull spears and wipe away blood from his body, or do you ignore these superficial concerns to get to the next puzzle? Trico isn’t your typical AI because he adjusts his behavior according to your own. He has feelings and needs, and to ignore them is to miss the game’s point. You set an example to Trico as his master, and benevolence and humility should follow, especially since he’s half of the reason you’re able to get anything done. The relationship goes both ways. If you trust Trico, he trusts you, which brings up plenty of moments where you sit on the edge of your seat jumping into nothing, hoping that the beast will catch you safely.

I say this because I approached the game in this manner. You interact with Trico by telling him which direction he should go in and what action he needs to perform to help complete puzzles. Most of them are simple enough, but sometimes I felt like I exhausted my options. Instead of losing patience, all I had to do was keep trying. I believe this is why I had a shockingly easygoing time cooperating with my friend. The AI woes and 30-minute waiting sessions other critics speak of? There were only a handful of times where I was stumped for but a few minutes. Perhaps I got lucky. Perhaps others shouldn’t come into The Last Guardian expecting a smooth, fast experience, for if they do, they only exacerbate the intentional bumps in the road by responding poorly to them.

Former Kotaku writer Patrick Klepek got Ueda to admit that getting Trico to respond even upset him at times in development! “I’ll go ‘c’mon, just come over.’ [laughs] I get irritated. Then, I have to remember: if I’m a player who’s never played this game before and they call Trico over and he doesn’t respond, that’s the more realistic response. Trico’s an animal that doesn’t follow logic, the logic that we humans would, so it’s actually a positive thing. That’s the thing that I always need to keep in mind. The longer you play, the more logical you tend to try and make things, and that’s something we have to resist.” 2 When you embrace and appropriately react to the illogical design behind Trico, you uncover the internal logic of The Last Guardian, thereby bringing about the most optimal, joyous time because you learn how to train your Trico.

There’s something to be said for some of the lackluster puzzles and platforming in The Last Guardian. I didn’t find the former as involving or stimulating as Ico‘s puzzles. On the other hand, the latter isn’t as marvelous as the giant-climbing platforming in Shadow of the Colossus. This game is somewhere in between. It doesn’t exceed either predecessors in terms of its own puzzle design or action, but their worth is accentuated by how you connect with Trico at all times. That’s what elevates the gameplay slightly above the sum of its parts.

I adamantly stress that the game does not get a pass everywhere else though. I love how unique the AI is and how it prompts you to treat Trico unlike any other game companion, but why in heaven’s name are the controls and camera bad? With the former, I was disappointed by the thresholds set for the analog stick with movement. There are two speeds: tip-toeing and 0-to-100-real-quick sprinting. This is fine in itself, considering that Ico and Shadow of the Colossus are set up the same way, but the drastic variations in speed between the two and precision required to maintain tip-toeing with precarious platforming make some areas tough to navigate. I needlessly died multiple times because of this. In addition, the camera is floaty and lethargic, sometimes wrestling control from you to direct your attention in a contest of wills. It also resets and uncomfortably zooms in and out inside tight corridors.

Encounters with the stone guardians can be boringly one-note with you running around in circles to slowly open or unlock something in small increments, but when Trico is involved, they’re more engaging since you need to push guardians and pull spears from him to assist. And speaking of pulling spears, climbing atop his body works rather well. That is, until you get caught on his wings, legs, or tail on a regular basis. Some of these issues and the game’s general feel are what motivated some to say it feels like a PS2 game ported to the PS4. Well, it kind of is, and while I honestly like how the game feel a bit out of time, it’s no excuse for some of the aforementioned missteps. I also encountered two odd bugs and a couple frame rate drops on my standard PS4, but they occurred rarely and aren’t enough to warrant harsh feedback.

I didn’t experience horrible performance in my playthrough. Besides two jarring drops in the frame rate, the game runs at a fairly consistent 30fps. And it always look stunning.

Some of the puzzles were finicky with platforming and had unclear objectives. I didn’t exactly understand what the O and X buttons did with commands. There are other minor complaints I could list with The Last Guardian, but this can detract from what makes it such a special game in spite of its problems. You may not be able to look past them. You might. Either way, there’s an intrinsic magic here that casts its alluring spell on players like Ueda’s previous endeavors, but it’s the least effective out of them all, strong as it may be.

Visuals

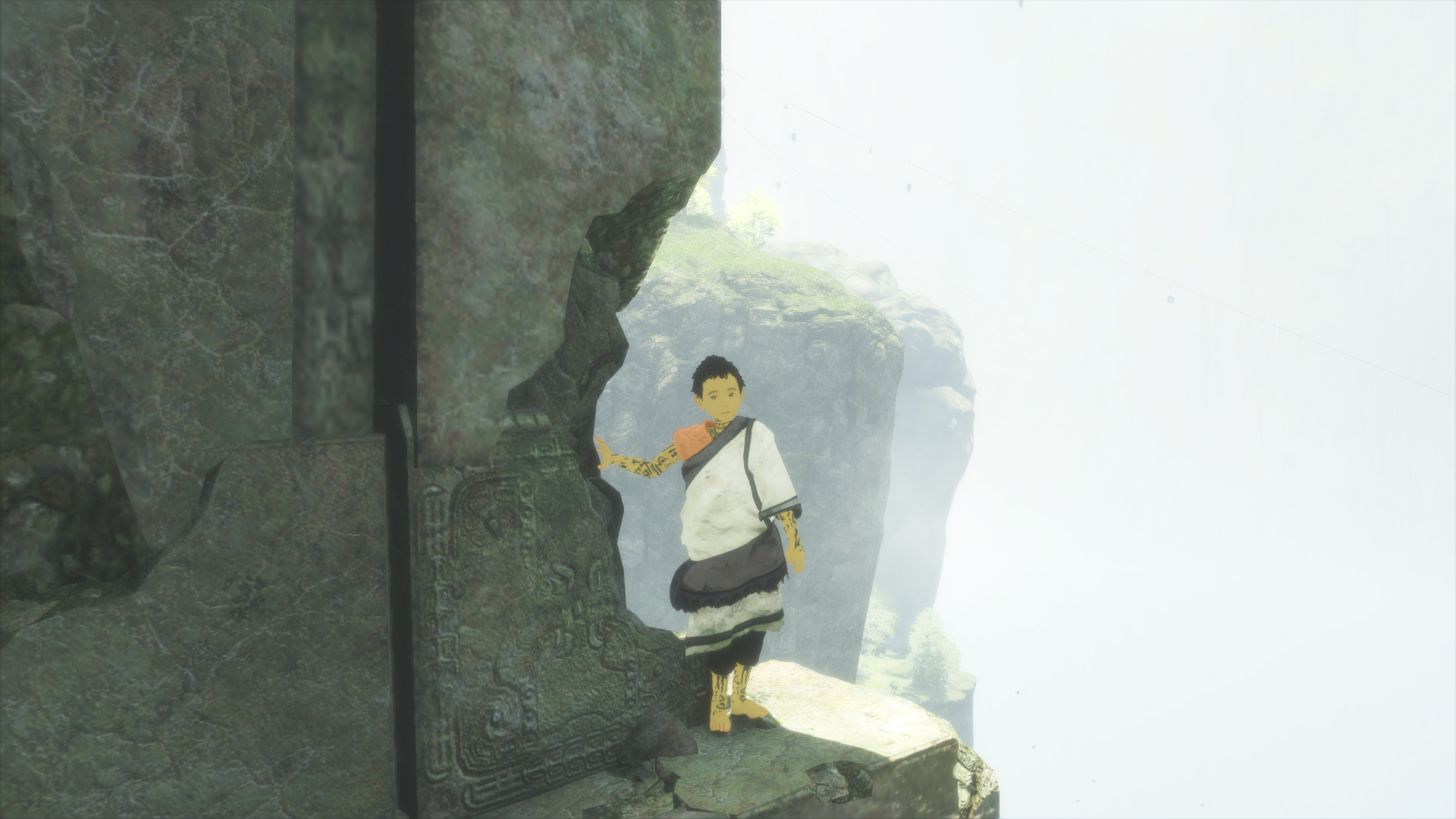

The animation of Ueda’s games have the distinct pleasure of being iconic for their expressive, loose quality. You would never notice looping or clipping since everything flows naturally, and The Last Guardian upholds this reputation. I was reminded of Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End and Inside, marveling at how cinematic and intricate the animation can be. For example, the boy will turn his head toward Trico when he’s around, touch walls when standing near them, and appropriately stumble with varying severity while vaulting over a fallen pillar or running over a small stone. What I mean to convey is that the game could play out like a seamless movie.

Trico is a more impressive feat, demonstrating some of the finest object collision I’ve witnessed. His feet and toes never clip through the ground; individual toes are slightly raised or lowered depending on where he’s standing. He always moves with power and grace. Rampant curiosity marks his motions, since he constantly inclines his neck or head toward objects of interest. His ears will slightly perk up when I call his name, and when I’m on his back and start rubbing his feathers, he’ll briefly tense, followed by loosening up as he closes his eyes in comfort. The feathers are beautiful as they individually rustle from the wind and specific movements, and Trico’s eyes relay what he’s feeling with different colors and sheens that express concern or even happiness. Whether we’re addressing a scripted sequence or a random moment during gameplay (like when Trico grabs you by the mouth and throws you onto his back), this beast looks and feels alive. I still choke up remembering how he behaves during a sobering point halfway through the story, which is the first time I shed tears playing a game mostly not because of the music, but because of what I was watching. I honestly get misty-eyed remembering it now.

My mouth dropped when the sun was setting in the later levels. The way the light casts on the spindly towers and across Trico’s feathers is gorgeous.

There’s a hazy, soft quality to the aesthetic, but beautiful lighting, physics, and expansive views counteract notions that genDESIGN lazily skimped on the visuals. Animation and realistic effects have always trumped sharp textures for this studio, and watching how bridges collapse, stained glass shatters, and light dances across environments confirm this observation. Even then, this is actually the most detailed title out of Ueda’s work with an attention to exotic, dreamy architecture. The structures are of Aztec origin, which seem like massive, complex Jenga towers with tunnels and rooms that are enigmas unto themselves with how they’re laid out. The idea this is an ancient, crumbling city is amplified by how greenery climbs the walls and rests atop debris, providing moments where nature’s claim over certain territories stops you in your tracks. Even the whitewashed stone of that tomb I mentioned and the central tower you venture toward feel otherworldly and unsettling, utterly contrasting the complexity of the surrounding architecture with smooth, rounded ceilings and archways. Their excessive tribal markings also thematically tie with the boy and the stone guardians. So yes, it’s hard to pinpoint and classify what this game draws inspiration from with its environmental design, but much like the story, the imagination on display is wondrous to contemplate, especially when you emerge from dark tunnels to find sprawling courtyards and chasms out in the bright light.

Audio

I appreciate the subtlety and nuances that went into the sound effects. The varied differences in the characters’ footsteps are prominent, from the light pitter-patter of the boy’s feet on different surfaces to the giant “thums” of Trico’s claws that make wooden bridges creak under his weight. You notice this because of how quiet the soundscape is, so minimal sound effects are magnified. Tranquility reigns in this realm. Instead of being drowned out, the sound of leaves and grass blowing in the wind are obvious, and the echo of water droplets and crickets in desolate caverns can be heard from afar. The Last Guardian inspires inner calm.

Trico’s distinct cries are strangely melancholic and sound like a mix of animals from dogs to whales. Even the boy’s voice changes tone in reaction to specific scenarios. He’ll sound worried when Trico is hurt, panicked when you both are fending off the guardians, and weary if he hurts himself from a fall. If you’re looking for ambience to fall asleep to or study with, just leave the game running in the background.

You can pet Trico. If you don’t do it when he nuzzles you, what kind of monster are you?

In being intelligently restrained and adaptable, the soundtrack is doubly emotional. If you’re caught by a guardian, another layer of strings will amplify the tension of the struggle as you wrestle to escape. And when Trico hops into the fight, the orchestra will adopt a victorious melody that overtakes the other’s nervous groove to symbolize that you’re no longer helpless. Music of a more excited sort always plays during stressed situations, but the regular gameplay is accompanied by nothing. Only pivotal moments that are moving on their own will be accompanied by chilling, Thomas Newman-esque music. It can suddenly fill the air, and it happens during the tearful scene I mentioned.

There’s more traditional instrumentation than we hear in Ueda’s previous games, but that doesn’t make the soundtrack any less beautiful. Just you wait until you hear the ending’s joyous track. The composer’s style of using a children’s choir, sweeping strings, percussion, piano solos, and the oboe throughout the score…I can’t find the words for it. Takeshi Furukawa doesn’t override the emotion the game conveys on its own, but adds to it only when the time is right. I nodded my head in agreement when he told Gamasutra that the “emotional aspects of the game were sufficiently conveyed by the stunningly expressive animations, and [I] felt that to further underscore it musically would be an unnecessary reiteration. To this end, the music avoids directly playing the emotional aspects instead highlighting the cinematic grandeur of the narrative and locale.” 3

Value

The Last Guardian is about 10 hours long. For what it is, it neither overstays its welcome or leaves too soon. It doesn’t feel padded out and didn’t leave me wanting more. You know how some indie games might only be a handful of hours, but are nevertheless worth your money for the powerful experiences they provide? I’d say the same for this game, which is already a substantial length and worth playing a second time to see how Trico might behave should you play differently. Trophies offer some incentive to replay the story, too. However, going through it once is more than enough. I believe this is an unforgettable experience all the same that everyone should embark on.

The eye of the storm.

Conclusion

Just like Ico and Shadow of the Colossus, many will grow fond of and be inspired by The Last Guardian for years to come. It’s a fairy tale that pulls on the heart strings with a whimsical world, provoking childlike wonder at every corner. After being in the stream of development for so long, it surfaces with dings and wear in the form of an unrefined camera and controls. Some unclear objectives and strange puzzles may be evident as well, but with a profoundly intriguing and lovable AI companion, stirring score, and captivating scenery and animation, it’s easy to see why this anachronistic anomaly was far too unique and precious to stay under forever.

Article Links: