Warning: This post contains some spoilers. You have been warned.

“He has given you two hands, one to give, and the other to receive.”

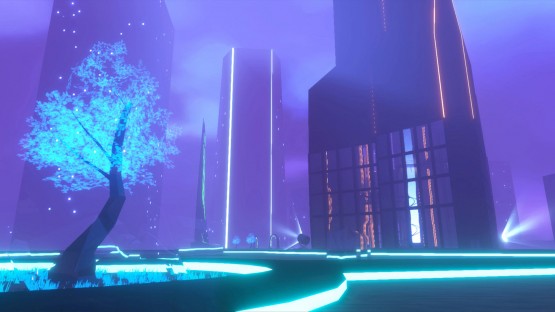

The more I attempt to understand Soul Axiom’s premise, the more I’m left befuddled. I come across this quote emanating from a portal of light, but I don’t know who “he” is or why I’ve been bestowed with power to bring specific objects into or out of existence. I don’t know who I am or why I’m here, but I can easily manipulate environments to suit my needs.

My character is a blank slate. He (or she?) has mysteriously found himself in a digital world called Elysia. It’s a depository for memories that can live on beyond someone’s life and be relived virtually by others. Players are tasked with retrieving the memories of particular individuals to slowly uncover what’s going on, and while those memories are abstractly represented with bizarre, unconnected locales and puzzles, you catch glimpses of the real memories by completing levels. As I unlock new abilities, I can rewind time and freeze objects, destroy obstacles with fireballs, and harness “deus” energy to mend incomplete memories.

It’s like I’ve got the whole world in my hands; I’m in control and carving my own path. But something feels wrong.

My grasp over these abilities is frustratingly flimsy and inconsistent. I begin to feel alone and watched, rather than the vicarious observer of these other characters’ pasts. In finding more of those quotes in tucked-away corners referring to a “G.O.D.” with power, sovereignty, and veiled ultimatums I must adhere to, I discover I am definitely not alone. The truth behind Elysia and the memories I discover unravel the plot of a megalomaniac, fixated on subjugating the very souls of humanity.

His name is Dr. Davies, a seemingly sincere, upstanding scientist attempting to broaden Elysia’s potential by discovering how to not only confine memories to the digital realm, but also souls themselves. Unlike the psychological horror game SOMA, Soul Axiom attempts to distinguish the properties of memories and souls as information vs. a fictional “type of energy unique from nature.” Rather than mixing the two together by categorizing the soul as equal to nothing more than encoded neural connections that can be stored on a memory chip, Soul Axiom invites the possibility of souls being one-of-a-kind phenomenons that can “dissipate in the ether.”

In other words, the soul is separate from memory. It’s a living conscious and personality not of this world, commanding yet being shaped by the carnal, temporal experiences of the body it’s bound to. Elysia is wholesomely purposed to record the latter for posterity’s sake, but Davies wants more. He surprisingly disregards blatant ethical considerations to advance his research in creating a device to trap the soul. He murders the homeless and ill patients in secret. He devolves into a sociopath narrowly focused on his obsession to create a conscious interactive record of humanity. He could literally play as a twisted God, either rejecting souls as unworthy for fickle reasons or imprisoning them in his own soul collection to study. It’s a special kind of Hell in itself described by real quotes throughout the game, twisted to replace mentions of God with Davies’ initials.

“There is no place in your soul, no corner of your character, where he is not.”

“Death is the prerequisite to resurrection, the new life G.O.D. intends.”

“G.O.D. is the friend of silence. See the stars, the moon and the sun, how they move in silence. We need silence to be able to touch souls.”

He even attributes Deuteronomy 32:35 to himself, concretizing the high view he holds of himself. He wants to be seen as a benevolent, merciful deity, when in reality, he’s a self-obsessed creature desiring to enslave souls to judge by works rather than grace. This is George Oswald Davies. G.O.D. The false god. As I realized the possible consequences of his actions, I knew my displays of power and intelligence would mean nothing to this delusional man if he came to deceive the world into the palm of his hand by providing a “sanctuary” for souls. In truth, those who naturally die are spared from an artificial eternity that denies passage into what really lies beyond.

C.S. Lewis speculated on a future where humans determine and control future generations through eugenics and pre-natal conditioning. This control over nature seemingly demonstrates our mastery over creation and our own destinies, but he asks, “The battle will indeed be won. But who, precisely, will have won it?” Indeed, he says that in doing this, the “Conditioners” who seek to preserve and propagate a humanity of their own design have sacrificed their own.

Davies is different in that he wants to control humanity beyond the grave, rather than brainwash and shape new lives. However, his goals are just as sinister and morally bankrupt as the Conditioners. The doctor proclaims that “without sacrifice there can be no progress. […] All actions are justified in the pursuit of knowledge.” And for those with this mindset, Lewis has some choice words about who they really are and what they gain in their pursuits.

It is the magician’s bargain: give up the soul, get power in return. But once our souls, that is, ourselves, have been given up, the power thus conferred will not belong to us. We shall in fact be the slaves and puppets of that to which we have given our souls. It is in Man’s power to treat himself as a mere ‘natural object’ and his own judgments of value as raw material for scientific manipulation to alter at will. The objection to his doing so does not lie in the fact that this point of view is painful and shocking till we grow used to it. The pain and the shock are at most a warning and a symptom. The real objection is that if man chooses to treat himself as raw material, raw material he will be: not raw material to be manipulated, as he fondly imagined, by himself, but by mere appetite, that is, mere Nature, in the person of his de-humanized Conditioners (72-73).

This game echoes a similar abolition of man, which you’re made well-aware of it by realizing your own character’s autonomy is on a thread should this come true. Davies falls to his own hubris in the end, but the dangers of god complexes like his becoming a reality . . . that’s the soul message of Soul Axiom.