David Cage is a meme. Other videogame industry figures like Todd Howard, Reggie Fils-Aimé, and Jeff Kaplan are jokes among gamers as well, but the difference lies in how these guys are usually teased in a playful, loving way. On the other hand, the humor surrounding others like Peter Molyneux, Phil Fish, and Randy Pitchford is typically deriding for various reasons. David Cage sits among them for his pretentious claims to produce deep, interactive, cinematic experiences that have broken down upon closer examination for many players. That’s not even mentioning other dubious circumstances the game director has been involved in, but I’m confident in accusing Cage of campy, stilted dialogue, meticulous mechanics that produce awkward or boring gameplay moments, and a couple more issues that others can articulate better than I could. I may have seen a good amount of footage and criticism covering his work, but I’ve never played one of his games through and through. That’s changed with Detroit: Become Human, so I naturally expected a cringe fest filled with bland interactivity. I came out of it … well, getting much less of that than I expected.

From the start, you’re put in the shoes of Connor: a prototype android with brilliant investigative and deductive skills. Another android has gone rogue and taken a girl hostage after discovering he’d be replaced by a newer model. This “deviance” has just begun cropping up among androids. It shouldn’t be possible for them to experience emotions, love, and moral compasses, but your assumptions surrounding the classic sci-fi debate about androids inform how you approach this life-or-death situation as Connor. You can investigate the child’s apartment at your discretion to increase the probability of talking the android down. Even then, you’re running against the clock in being thorough, which applies in engaging the android as well. Empathy, intimidation, cold logic – your dialogue options can slowly or instantly improve or doom your mission to save the girl. Whatever befalls Connor, you’ll still be gripping your controller tightly when the chapter’s storyline branches are presented. I was in awe of how much I missed … and how much I didn’t during that tense introduction.

There are simple detective scenes akin to the ones in Batman: Arkham City, but what makes Detroit‘s even better is how there are consequences to how quickly or effectively you pull evidence together, which can influence Connor’s fate, Hank’s perception of him, and so forth.

Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls ease you in, especially the former with its banal interactions to do things that bear little consequence. It’s an issue I’ve noticed with Quantic Dream’s games: there are too many button prompts, analog stick movements, and motion controls allotted to inconsequential actions. There’s room for that here and there, but a developer like Telltale Games knows when to cut back and lean heavily on simple interaction with its pedigree of titles. Supermassive Games showed how to give weight to characters’ fates with seemingly minor actions in Until Dawn with the “butterfly effect” approach to its narrative. A character picking up an item or choosing to spare an animal could make all the difference, pushing players to be cautious and thoughtful. As for Detroit, it still contains plenty of those notoriously excessive, shallow QTEs (I hate it when they chop up the otherwise gorgeous, fluid animation), but I felt my curiosity and exploration mattered more this time around. I think that stems from Cage honing his art of believable, sprawling storylines by, if you will, creating small twigs that can turn into sprawling branches or bring down the larger ones they grow from. In other words, minor oversights and perceptive observations I made throughout the three main characters’ arcs genuinely surprised when I discovered how they influenced the paths I forged.

Connor is one of those main characters, who’s assigned to help a hard-boiled detective solve deviance by taking on exciting, diverse cases that not only question your perception of androids’ free will and supposed humanity, but also involve the trials of befriending your rundown yet endearing human partner. Kara is a housekeeping android who breaks protocol when her owner abuses his daughter, resulting in a game of hide-and-seek to escape from Detroit while becoming an unconventional parent. Markus is a caretaker android who finds himself embroiled in an androids’ rights cell, putting you in the philosophical struggle of choosing to face injustice with peace or violence (my favorite of the three arcs for its genuinely challenging conundrums and ramifications).

What makes Detroit unique in the “are androids people?” theme category is how everyone you control is an android. Like usual, you’re watching or playing as a human challenged about their view of androids like usual. Here, you are the androids questioning who they are and should be. What would you do in their shoes? It’s a question perfectly suited for a videogame to exploit … one that, to my knowledge, hasn’t been explored in any sci-fi media from this unconventional angle.

It’s blatant that Cage is drawing parallels to racism and, specifically, the Civil Rights Movement with androids standing in the back of buses, signs on businesses banning androids, Martin Luther King Jr. references, and even an allusion to Michael Brown with the option to have Markus’ androids adopt a “Hands up, don’t shoot” gesture toward police. The game’s setting is telling enough of how unsubtle Cage is with the points he’s trying to make. Even though it’s farfetched and on the nose to conflate actual human beings (and their struggles) with androids, I can buy how the latter’s struggles with equality would be generally similar if they came to pass in reality. After all, it’s not like there aren’t relevant examples (see Ex Machina, Blade Runner 2049, Nier: Automata, iRobot). Detroit doesn’t bring much to the table that other media haven’t adequately covered before, but to say the game’s devoid of interesting, compelling situations playing on the theme would be disingenuous. Some of the best stuff is – shockingly enough – on the main menu, which … shall we say, responds to your choices.

I don’t think Cage botches it here, though I imagine he’d fare better sticking with his knack for nailing complex, evolving character relationships and dynamics (here and there) rather than focusing on saying something through them in a messy way. So yes, some of the writing may sound unnatural. A couple characters’ motives and development are strange (I’m looking at you, Hank and North). There are jarring, logical inconsistencies in the world (with what androids can and cannot do, when the story takes place, etc.). Despite these problems making me shake my head in confusion, I was pleasantly surprised by the balancing between all three arcs and how they intertwined. The beginning drags a bit after Connor’s chapter (it’s a hard one to top), but the action, investigation, dialogue, and exploration eventually equalize at a start-and-stop pace I struggled to pull away from as the stakes increased over time. It helps considering how this might be Quantic Dream’s best cast of actors yet. They truly bring out the characters’ individualities and personalities. I feel compelled to go through the game again not only to see how other choices would’ve played out, but also to see how the actors shift in tone with alternative responses and actions.

Hank and Conner had the most satisfying, even humorous relationship throughout the story. “My story” for the duo was focused on building Hank’s trust not just in androids, but also Connor’s genuineness. Unlike some games’ vague or misleading dialogue options, I felt that my selections felt true to their brief descriptions. I can’t help but think of similarly entertaining scenarios with Nick and Judy in Zootopia or Baymax and Hiro in Big Hero 6. You’ve got the one person with an internal/external struggle and the unconventional buddy that comes in and changes their life for the better … after some bumpy roads, of course.

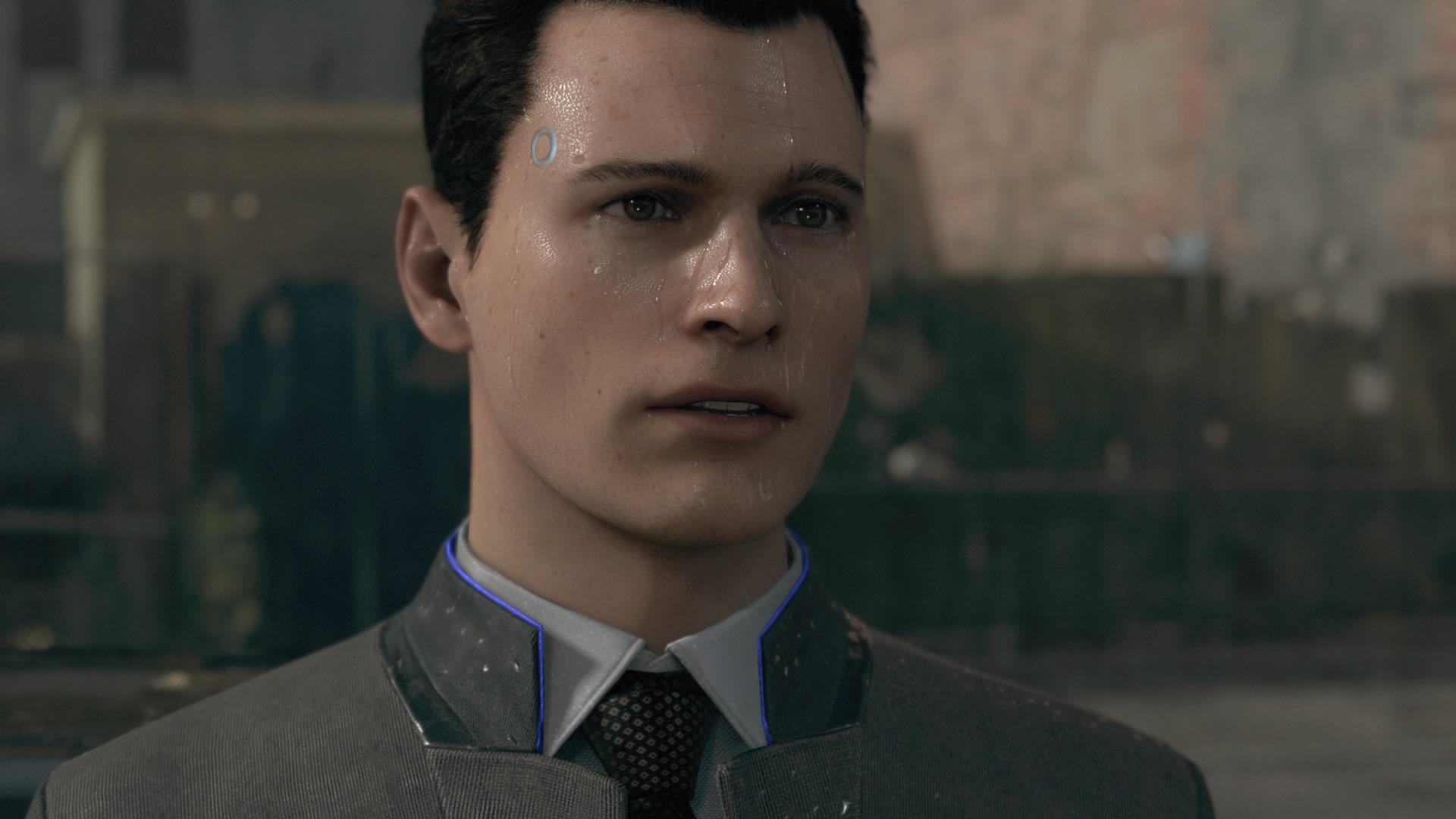

You wouldn’t think that Detroit would be among the most glamorous locations to explore in videogames. Turns out that Quantic Dream’s team of artists bring Detroit to a whole new level with believable advances in technology regarding the city’s infrastructure and architecture. Even the worn-down, lower-class neighborhoods remain, which help set some of Detroit’s historical woes in reality. I also have to gush over the fashionable costume design and impeccable character models. I was witnessing Naughty Dog levels of detail with individual rain droplets sliding down and glistening on faces. There’s gorgeous lighting and subtle details to animation that blew my mind (e.g. Connor stepping over objects on the floor). Even though my quibbles with the gameplay remain, Detroit can be a visually astounding, cinematic ride worth getting lost in. Did I mention the score has some standout piano melodies, killer synth, and superb electronic ambience? As I implied, I think Quantic Dream has struggled before with vision and focus. Not as much this time.

Would ya just LOOK AT IT.

Would ya just LOOK AT IT.

Conclusion

I despise forming preconceptions without personally going to the source or getting the full story. Negative notions of Cage and his games got to me, but when I unplugged from Detroit: Beyond Human, I was charged with more respect for the distinct creations that Quantic Dream contributes to gaming. The game retains that signature vibe of eccentricity and awkwardness from its predecessors by overly relying on minimal interaction and being hampered by flawed writing. Regardless, the story contains bits of brilliance and emotional resonance, brought out by entertaining characters in a tale of ambitious scope. It’s rare when I replay videogames, but this might have to be one of them due to a slew of scenarios that I never even got to see. I feel like I only got to experience half of what this game can offer. If the first playthrough leaves me wanting more, that’s a testament to its value, and Detroit has a solid amount to give if you give it a chance.